DIY an on-disk B+ Tree

If not, here’s a visual crash course on the operations of a b-tree and generally on-disk considerations. or a much better walkthrough with sqlite

What is a Datastructure’s memory representation? Everything is either a contigous block or pointer based. Relevant programming techniques: pointers, recursion and binary search - Olog(N) is powerful, syscalls and binary formats.

B-Trees are useful for:

- In-memory indexes/‘index b-trees’ (also used here!)

- persisted on disk storage organisation/’table b-trees’. <– we’re here.

Why is it called a B-Tree? According to one of the co-inventor’s Edward M. McCreight it’s short for “balance” – but could mean anything :)

Implementation high level ideas

Considerations:

- Performance (Access Patterns - everything is about access patterns)

- Correctness & Testing

- Durability (what’s a block?, brief overview: buffered IO, mmap, directIO.)

performance big ideas overview:

- why do we want search trees? balancing and order

- going beyond Big-O - logarithmic acess.

- mutability vs immutability

- concurrency

- locality of reference(time/space) (keep stuff close togther)

B Trees (In-Memory)

A simple and useful way of thinking of access and logarithmic bisection is a Tree of a 2-D array:

[[1,2,3], [4,6], [9,11,12]]

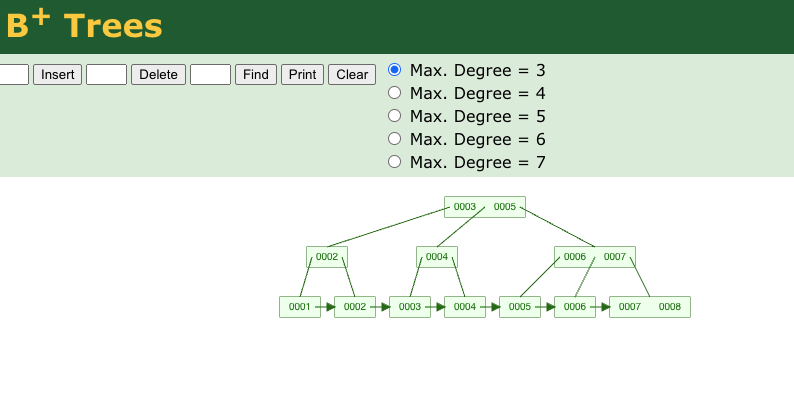

visualisation: https://www.cs.usfca.edu/~galles/visualization/BPlusTree.html

desired properties:

- high fanout (dense trees)

- short height

/*

Simple Persistent B Plus Tree.

Node keys are assumed to be signed integers and values also.

Persistence is achieved using a naive bufio.Writer + flush.

Concurrency control using a simple globally blocking RWMutex lock.

B-Tree implementations have many implementation specific details

and optimisations before they're 'production' ready, notably they

may use a free-list to hold 'free' pages and employ

sophisticated concurrency control.

see also: CoW semantics, buffering, garbage collection etc

// learn more:

// etcd: https://pkg.go.dev/github.com/google/btree

// sqlite: https://sqlite.org/src/file/src/btree.c

// wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B%2B_tree

*/

Definition:

A B plus tree with an arbitrary max degree 3, degree is the number of pointers/children each node can point to/hold:

const (

MAX_DEGREE = 3

)

const (

ROOT_NODE NodeType = iota + 1

INTERNAL_NODE

LEAF_NODE

)

type BTree struct {

root *Node

}

A node:

type Node struct {

kind NodeType

// maintaining a parent pointer is expensive

// in internal nodes especially

parent *Node

keys []int

children []*Node

data []int

// sibling pointers these help with deletions + range queries

next *Node

previous *Node

}

Operations Overview:

- access

func (n *Node) basicSearch(key int) *Node {

if len(n.children) == 0 {

// you are at a leaf Node and can now access stuff

// or this is the leaf node that should contain stuff

return n

}

low, high := 0, len(n.keys)-1

for low <= high {

mid := low + (high-low)/2

if n.keys[mid] == key {

return n

} else if n.keys[mid] < key {

low = mid + 1

} else {

high = mid - 1

}

}

return n.children[low]

}

- insertion/split algorithm

func (n *node) split(midIdx int) error {

// first find a leaf node.

// every node except the root node must respect the inquality:

// branching factor - 1 <= num keys < (2 * branching factor) - 1

// if this doesn't make sense ignore it. The take away:

// every node except root has a min/max num keys or it's invalid.

// edge case, how to handle the root node?

// node is full: promotion time, split keys into two halves

splitPoint := n.keys[midIdx]

leftKeys := n.keys[:midIdx]

rightKeys := n.keys[midIdx:]

n.keys = []int{splitPoint}

leftNode := &node{kind: LEAF_NODE, keys: leftKeys}

rightNode := &node{kind: LEAF_NODE, keys: rightKeys}

n.children = []*node{leftNode, rightNode}

// -- LEAF

// (internal node(left)) (internal node(right))

// \ /

// (current leaf node)

// recurse UP from curr to node which may overflow,

// check that we're not full if full, we split

// again allocate a new node(s)

// --snipped for clarity

return nil

}

- deletion Two operations, steal/redistribution/rebalancing and merging:

func (n *Node) merge(sibling *Node, key int) error {

// delete data from leaf node

// steal sibiling fist, if underfull --snipped

// do stuff to prepare for merging, assume we _can_ merge

// deallocate/collapse underflow node

sibling.data = append(sibling.data, n.data...)

for i, node := range sibling.parent.children {

if node == n {

n.parent.children = append(n.parent.children[:i], n.parent.children[i+1:]...)

}

}

// recurse UPWARD and check for underflow

for i, k := range sibling.parent.keys {

if k == key {

sibling.parent.keys = cut(i, sibling.parent.keys)

if len(n.parent.keys) < int(math.Ceil(float64(MAX_DEGREE)/2)) {

f sibling, _, err := sibling.parent.preMerge(); err == nil {

return n.parent.mergeSibling(t, sibling, key)

}

} else {

return nil

}

}

return nil

}

B Trees (Going to Disk)

Cannot reference memory using pointers. Can no longer allocate/deallallocate freely.

We read/write/seek to the operating system, in fixed size blocks, commonly 4KiB - 16KiB.

Classic B+Tree paper uses a triplet -{pointer/offset to child, key, value}, limited by fixed size storage (fragmentation is difficult).

the “classic” datafile layout:

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+ header | {p1, key1, value1}, {p2, key2, value3} .. +

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Slotted Pages are common in most database row/tuple oriented implementations such as SQLite and Postgres. Slotted pages are used to solve the problems space reclaimation and variable size data records. In columnar format encoding such as parquet a modern variable length encoding is used and a dictionary maintained of data pages that is compressed and tightly packed.

For e.g the page layout in postgres:

The logical view of the datafile:

[header (fixed size)] [page(s) 4KiB | ...] [trailer(fixed size)]

show me the code - the high level “page”:

// Page is (de)serialised disk block similar to: https://doxygen.postgresql.org/bufpage_8h_source.html

// It is a contigous 4kiB chunk of memory, both a logical and physical representation of data.

type Page struct {

header header

cellPointers []int16

cells []cell

}

its fixed size byte page header:

type pageHeader struct {

// Represents a marker value to indicate that a file is a Bolt DB.

// copy/pasta as a magic number is 'magic' and kind of madeup.

magic uint32 // 4 bytes

PageID uint32 // 4 bytes

Reserve uint32 // 4 bytes

FreeSlots uint16 // 2 bytes

// the physical offset mapping to the begining

// and end of an allocated block on the datafile for this page

PLower uint16 // 2 bytes

PHigh uint16 // 2 bytes

NumSlots byte // 1 byte (uint8)

// all cells are of type CellLayout ie is key/pointer or key/value cell?

CellLayout byte // 1 byte (uint8)

pageType byte

}

and finally the cell:

type cell struct {

cellId int16

keySize uint64

valueSize uint64

keys []byte

data []byte

}

naively flushing a page + fsync:

func (p *Page) Flush(datafile *os.File) error {

buf := new(bytes.Buffer)

_, _ := datafile.Seek(int64(p.PLower), io.SeekStart)

binary.Write(buf, binary.LittleEndian, &p.pageHeader)

binary.Write(buf, binary.LittleEndian, &p.cellPointers)

binary.Write(buf, binary.LittleEndian, &p.cells)

buf.WriteTo(datafile)

datafile.Sync()

log.Printf("written %v bytes to disk at pageID %v", n, p.PageID)

return nil

}

and fetching it back:

const pageDictionary map[int]int

// --snipped, tldr; hashmap conceptually

// maps the page ID to an actual offset

func Fetch(pageId int, datafile *os.File) (Page, error) {

var page Page

datafile.Seek(pageDictionary[pageID], io.SeekStart)

err := binary.Read(datafile, binary.LittleEndian, &page.pageHeader)

return page, nil

}

There’s some cool optimisations we can do!

Miscellaneous

- magic numbers: For e.g boltdb’s magic number - tldr; random number to uniquely discern bin data reads.

const magic uint32 = 0xED0CDAED

See the demo repository for more examples!

Future, Maybe Never :)

- The pitfalls of memory: allocation, fragmentation & corruption

- concurrency mechanisms - snapshots, OCC/MVCC

- async split/merge/delete

- BTStack/Breadcrumbs

- lazy traversal: Cursor/Iter

- more optimisations/variants: B-link, CoW B-Trees, FD-Trees etc

- robust testing and correctness guarantees

- se(de)serialisation to network (replication)

- DIY a freelist!

- IO_URING/async direct/IO

- durability! DIY a WAL or smaller "rollback journal"

- good benchmarking & profiling etc see tools of the trade

Tools of the Trade

Base your judgement on empirical fact:

- a good debugger or not (gdb etc)

- flamegraphs

- benchmarking

- tests - unit, integration, fuzzing, proptests, simulations etc

Performance comes from thinking wholistically about hardware and software together. Optimizations bear the fruits of pretty benchmarks and complexity. The first big piece is concurrency and parallelism.

tldr; the hard part about building storage engines is debugging and testing them, old databases are good because time spent in production uncovering (or not uncovering bugs).

In the real world stuff goes wrong(the operating system hides hardware and software faults, but you have to care), data loss is bad and is a big no-no.

Running in production: Correctness, Testing & Safety

Complexity is evil but unavoidable, non-determinism makes you helpless.

testing methodology, loom - concurrency is hard etc:

- How SQLlite is tested: https://www.sqlite.org/testing.html

- Valgrind, Address and Memory Sanitizer

- https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~bornholt/papers/shardstore-sosp21.pdf

- https://github.com/tigerbeetle/tigerbeetle/blob/main/docs/DESIGN.md#safety

- https://apple.github.io/foundationdb/testing.html

- many more…

Further reading: storage engine architecture

Move towards modularization of database components, decoupled query & execution engine(velox, datafusion etc), storage engine see: foundationDB.

What the heck is going on in your favorite database? select/biased popular deep dives into popular storage engines for: postgres/postgres, kubernetes/etcd, mysql/InnoDB, mongodb(WiredTiger):

postgres: https://postgrespro.com/blog/pgsql/4161516

etcd: https://etcd.io/docs/v3.5/learning/data_model/

innodb: https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/8.0/en/innodb-physical-structure.html

mongodb: https://source.wiredtiger.com/11.2.0/arch-btree.html

Things we’ve come to want/expect out of modern databases:

- Seperation of Storage and Compute: https://clickhouse.com/docs/en/guides/separation-storage-compute

- Multitenancy: https://github.com/neondatabase/neon/blob/main/docs/multitenancy.md

- Distribution/Replication: Availability, Redundancy & Serverless style scale

- DBaaS/Cloud Native Stateful Backend services + Database engine, supabase etc